The best moment was probably the first. I stood with my assigned clan (Caithness) at the imposing wooden doors to the main Drill Hall at the Park Ave Armory. A hooded figure blocked our way. He bellowed, "What clan is this?" We shouted "Caithness!" none of us quite knowing how to pronounce it (I may have shouted "Katniss"). The door opened, our clan leader beckoned, we entered the hall, and then were in another world. The floor was a stone path in an immense open field, lit by shadows and fog — a heath, a moor, whatever you call it. The hooded figure walked in front of us briskly with a torch and we followed. Ahead of us — a henge of stone, a stonehenge. The outside boundary for the traverse stage of Rob Ashford and Kenneth Branagh's Macbeth. The path diverted, and we went up the stairs of the bleachers to our seats.

New York, for better and worse, is such a distinctive place. Most New York theatre doesn't worry about this, or otherwise embraces the city's natural environment. When in a theatre we feel the familiar: we know where we are down to the cross street, we know what's expected of us, we recognize these people ("...actors," we say, and sigh). But the Armory is such a unique location — a building the size of a city block — that it doesn't feel like the city anymore. There just aren't expanses like this. And so, entering the drill hall can feel like entering another world.

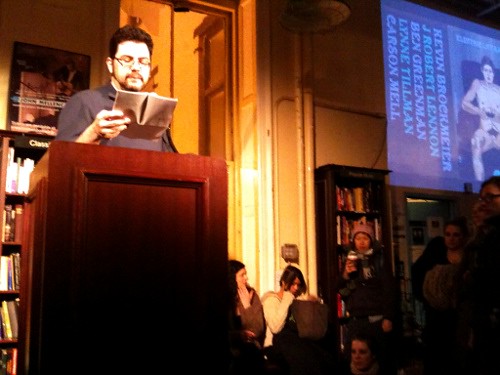

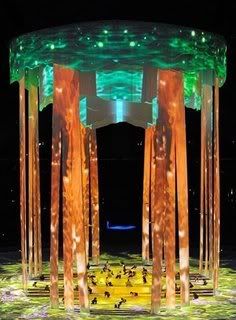

The actual stage took up about half the space of the Armory, with the other half making up that ever-impressive heath. The audience sat on bleachers on either side of a narrow lane of mud. On one end of the lane, a stone chapel with gleaming cross. On the other, the henge, where the witches vamp and levitate. My clan sat in the worst possible place, as high up and to the right as you could go without falling over the wooden slats to your death. But then, my clan has always been known for frugality.

The pit of rainy mud, the assigned clans, the complimentary drinks, all gave the affair a Medieval Times feel (though sadly we had to leave the wine outside). And that seemed strangely appropriate. After all, Shakespeare's theater wasn't the pristine, elderly-accessible place it is today. He was all for spectacle and roaring, ale, fights, lewdness. A Macbeth where we could cheer and gasp and shudder and get splattered in stage blood would be kind of wonderful.

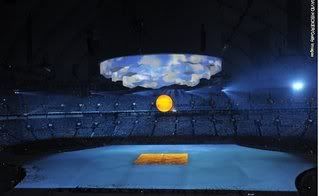

|

| He's having Wild Wild West flashbacks |

But even before this I noticed problems. Prior to the show we were supposed to meet with our clans in some of the lovely side rooms at the armory. (Mine was right by the complimentary wine table, which made me know I was among kin.) But besides all of us standing in the same room, there was little solidarity. And the usher assigned to act as clan leader and get us ready to move to the drill hall wasn't exactly playing up his role, and for good reason: the more into character he got, the more the Park ave crowd chuckled and sipped their wine and made snarky comments. So, maybe this is not the venue for immersive theater? Or, is caustic irony just a fact of the theatregoing audience today? Breaking down resistance to mystery is one of the hardest parts of putting on a show, and it is doubly hard when you're asking your audience to do more than they usually expect to do. Sleep No More solved this with masks — because maybe behind a mask people less feel the urge to be an asshole.

The production itself held few surprises. I'd never seen Branagh on stage before, but on stage he was little different from his many Shakespeare films. Branagh's a fine actor but a limited one, and there is precious little difference between his Henry V and his Benedick, his Hamlet and his Berowne. He is also often guilty of a very bad habit which extends to entire casts when he directs. He delights in the music of Shakespeare's language, crafting every syllable to great effect as he delivers word after word in a sonorous cascade of verbiage. Meanwhile conveying precisely none of the meaning. A common failing, sure, but of late there have been so many wonderful local Shakespeare productions that put great thought into both the music and the meaning, so it's a bit disappointing to see a throwback like Branagh again, declaiming and posturing. Particularly disappointing was the "Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow" speech, which was beautifully delivered but immensely unmoving. The weighty silence he left before the speech actually spoke far more than he ended up saying. Which is certainly not the fault of the writing.

Oddly, it was in the fourth act that most lagged. Here is where Macbeth largely disappears and we get a wider sense of the world and the effects of his tyranny. Richard Coyle's MacDuff had the gruff gravitas to carry his scenes, but there was a focus lacking here that pointed toward what was largely missing in the show. Macbeth needs to be so big that his absence is almost a joy. Here, he was hardly missed.

Macbeth, of course, is so well-written that it would take a supreme effort to make a bad version of it and this was by no means a bad version. And maybe my spot in the nosebleeds took me too far from the action for the actors to have much resonance — the people up front were so close to the fight scenes that you feared for their lives at times. If we had felt less like an audience and more like a clan, yelling and cheering on our chosen representatives, then maybe the sheer force of all these people could have imbued the stage with more heft. But the fact of such a big set demands a bigness of character that was lacking here. Sure the cast was enormous and the fights were epic and the henge was imposing and Alex Kingston always looks good in a red dress. But the humans in it were kind of small.